Why China-Russia relations are warming up in the Arctic

China needs Russia for its Polar Silk Route ambitions; Russia needs China as it tries to reclaim the Baltics

How China’s Polar Silk Road can make Canada the next big Asian power

The intention is a massive extension of Beijing’s influence, by means of Chinese infrastructure projects in countries along the routes, done at bargain prices in return for a share in the power or proceeds that the projects generate.

Why is China adding the Arctic into the mix? The Arctic has 30 per cent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13 per cent of its undiscovered oil reserves. But “undiscovered” is the key word – no one really knows what is there. Access to resources is made more difficult by the size of the vast polar region and its remoteness. The area within the Arctic Circle is 20 million square kilometres, more than twice the size of China.

It’s also very difficult to operate there; extreme cold requires extra equipment for humans and machines, communications with home bases are much harder and crew fatigue is a problem due to the pitch black winter days and white nights in the summer. But despite the obstacles, the Arctic is an important potential source of fuel for any nation willing to play the long game, and China plays the long game very well.

China’s other declared interest is in navigation. The white-paper plan would take advantage of the environmental damage caused by industrialisation – the melting of the ice. Ships may eventually be able to travel through previously inaccessible icy areas. Some of the quickest air routes from city to city are across the North Pole, so it might be possible to create new sea routes taking the same short cut.

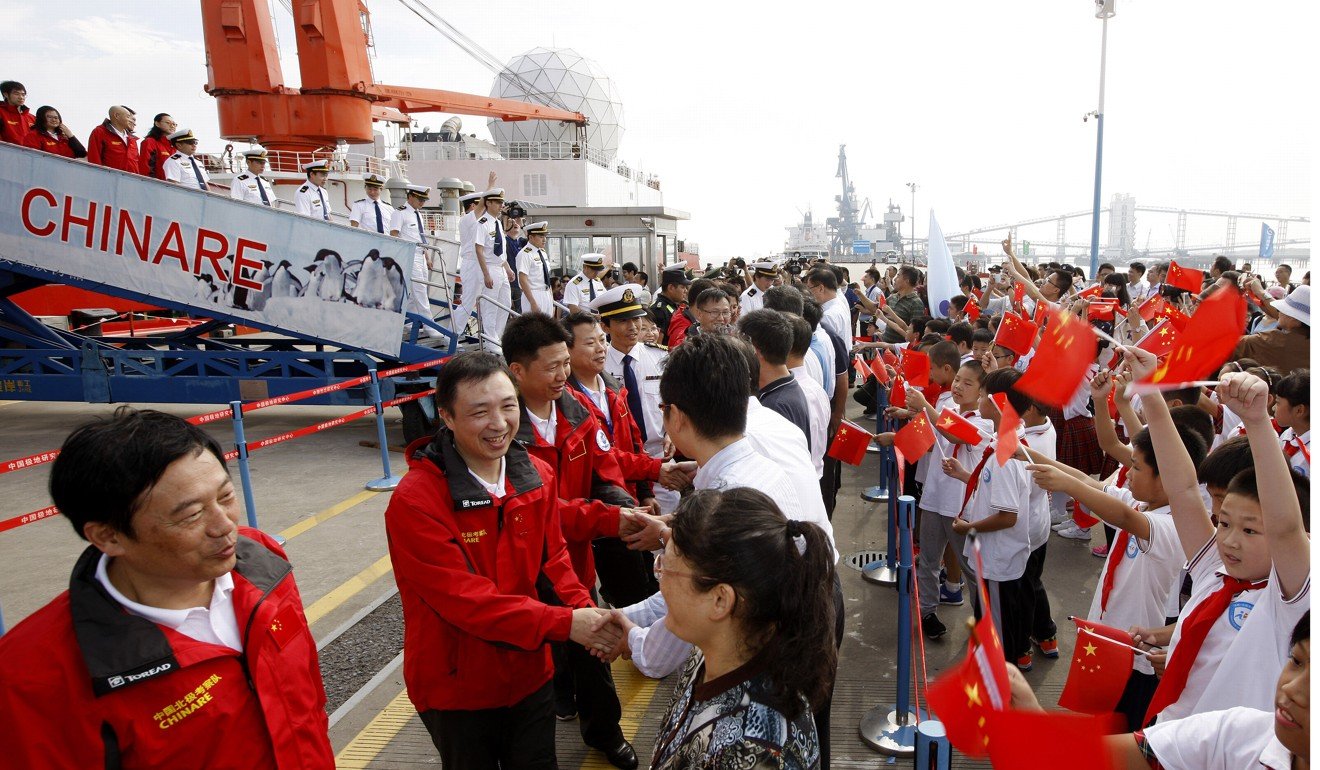

China’s polar research vessel Xuelong has already made journeys along the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route, along Russia’s Arctic coast, in 2012 and 2017. At present, Chinese shipping to Europe must go past Singapore (through the Strait of Malacca) into the Indian Ocean, and then up the North Sea and into the Suez Canal. This takes five weeks, compared to just three weeks for the proposed Arctic route. China has started building a second ice-breaker, the Xuelong II, which will launch next year.

According to Mia Bennett of the Maritime Executive, China is using subtle means to exert its presence in the polar region. The three Arctic shipping passages it wishes to develop, along Russia, Canada, and over the top of the North Pole, include two that they have “slyly” renamed – they do not refer to them as the Northern Sea Route or the Northwest Passage. “In fact, basically, the Northern Sea Route has been renamed the Polar Silk Road, and I’m not sure how Russia’s Northern Sea Route Authority will feel about that,” says Bennett.

How China and India can keep the peace in Ukraine

Recently, however, these Nordic countries have become a little less welcoming. When a Chinese company tried to buy a privately owned former military base on Greenland last year, the Danish government hurriedly bought the base back to prevent it from falling into Chinese hands. China also appears to be planning to buy two ports in Iceland, as well as Norway’s Arctic Kirkenes port, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, but these projects may now be stymied.

China was granted observer status on the Arctic Council in 2013, which brings it closer to the region’s governance process. The council comprises eight countries bordering the Arctic: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Russia, the United States and Iceland. And although the Central Arctic Ocean is indeed uninhabited and considered part of the high seas under international law, areas close to those countries fall within various types of national control or influence under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

So the Arctic is not the free-for-all that its remote and uninhabited nature might suggest. Of the Arctic Council nations, the largest (and perhaps most likely to ally with China) is Russia.

Russia is a difficult country for foreign investors, who are not allowed to export any resources they extract, a perk only allowed for state-owned monopolies Gazprom and Rosneft. It is pursuing a new onshore gas project on the Yamal peninsula, but most future plans of offshore oil drilling in Russia have been halted, or at least hampered, by Western sanctions.

This gives plenty of opportunity to China, and the China Development Bank will invest in the Russian energy giant Novatek’s Arctic LNG II, giving China access to Arctic liquefied natural gas. But more importantly, the deal will give Beijing the right to demarcate sectors of the Arctic within Russia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for Chinese exploration.

In Afghanistan, Putin courts China in search of ‘another Syria’

According to Camilla Sørensen and Ekaterina Klimenko of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russian companies need and welcome Chinese investments and loans, but are not comfortable allowing Chinese companies to play a major role in Russian energy projects, including those in the Arctic. Chinese companies, by contrast, are in a very strong position at the moment and would not agree to anything less than a significant control and management role.

It has been argued that there is little economic motivation for Chinese companies to push into the Arctic and make concessions of any sort to Russia, and yet somehow they have appeared in the Arctic already.

The answer lies in politics. It may be true that Chinese companies are hard to bargain with, but politically, the dynamic is very different. Chinese politicians need to provide energy and other resources for the population for the foreseeable future, so are more willing to make concessions than might be commercially desirable. What has China offered Russia in return, to ensure that it gets treated differently to other foreign countries? The answer lies in the Baltics.

China has already dispatched its navy to the region to cooperate with Russia’s in the Joint Sea-2017 exercise, which allowed Beijing to show political support for Moscow’s security interests in the region. For Russia, this show of political support from a major power is useful for strengthening its position in dialogues with Nato.

Nato’s absorption of the three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) caused great resentment in Russia, not least because Nato now sits between Moscow and its enclave of Kaliningrad. There are several thousand Nato troops in the Baltic nations, with Britain supplying the largest contingent. Though massively outnumbered by the Russians, who have already held mock Baltic invasion exercises with up to 35,000 soldiers, the British regiments, the Canadians in Latvia and the troops of several other nations would present a deterrent. Added to that is the US military presence in Poland; although they are 600km from where the front line would be, they could be moved forward quickly.

Chinese in the Russian Far East: a geopolitical time bomb?

China’s desire to keep Russia at odds with Nato goes back a long way. In 2003, the China Institute of Strategy and Management set the tone with an influential article “Russia could join Nato – and I’m not joking.” This was a nightmare proposition for China; the idea of two military superpowers allied, potentially against China, motivated Beijing to draw Russia as close as it could. Its remaining border disputes with Russia were solved the following year and China has consistently voiced approval for the actions of Putin’s Russia. Noticeably, however, it did not approve of his annexation of Crimea, since to do so would be to approve the regional plebiscite that resulted in the region’s secession from Ukraine and therefore justify the holding of a similar vote in contested regions of China. But it has made up for this in other ways; other points of interest include China’s construction of a town near St Petersburg (called the Baltic Pearl), and its joint naval exercises in the Baltics last summer.

Buoyed in part by China’s approval, Russia commenced last year the kind of activities it carried out prior to its Ukraine intervention in 2014, but this time aimed at the Baltic states. It stepped up a campaign of disinformation in Russia, and according to Lithuania’s Defence Minister Raimundas Karoblis, the Kremlin has been offering historical reasons why the cities of Vilnius and Klaipeda should not belong to Lithuania. Social-media campaigns have also charged that Vilnius is mistreating ethnic Russians. Russia has also reinforced Kaliningrad, possibly hoping to block or delay any US movement from Poland to reinforce Nato in the Baltics.

Neither China nor Russia have a habit of transparency in their long-term policymaking. Yet Russia has a track record of boldness, verging on recklessness, in its military interventionism. China has no such track record, but, despite its avowed (and sincerely meant) commitment to stability, it might be perfectly content to give the nod to more adventurism for Russia if, in return, it can achieve a free hand in the Arctic.