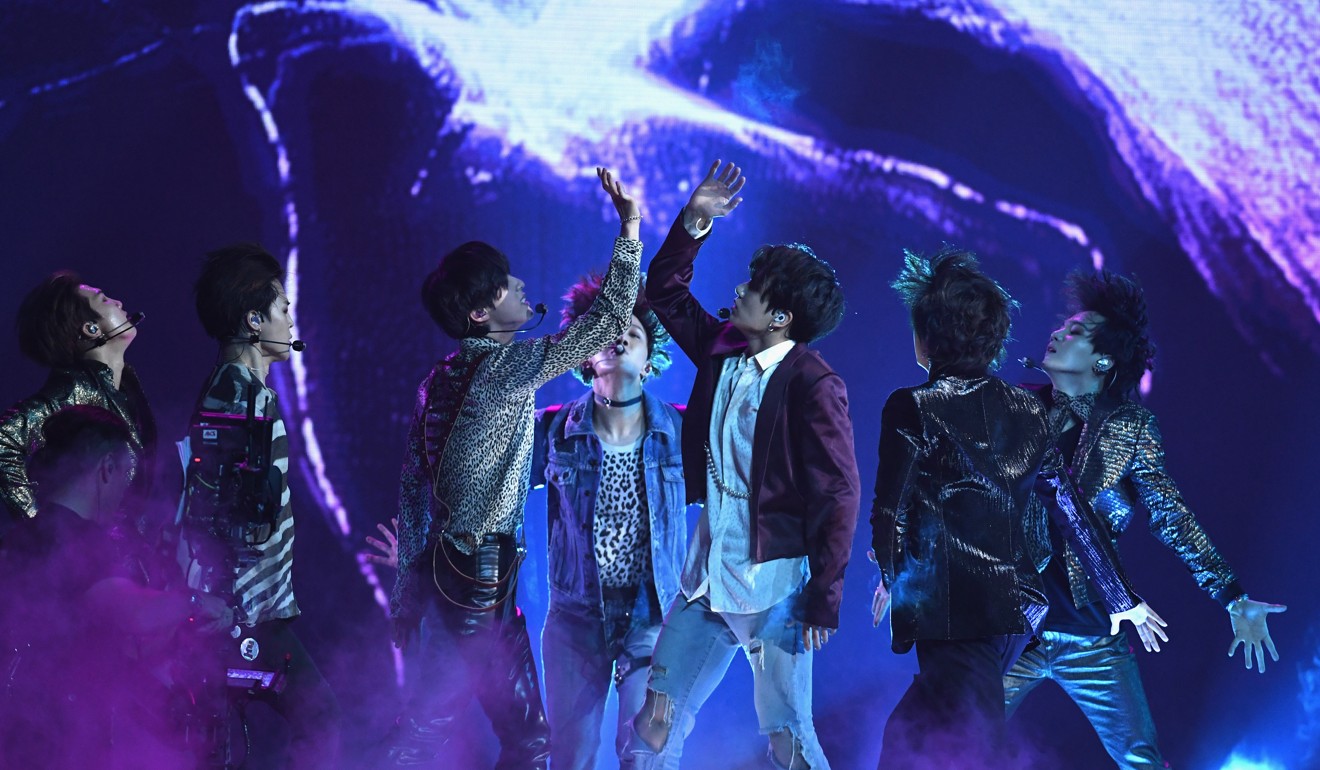

Girls’ Generation to BTS: how K-pop swept the world – and the UN

When boyband BTS spoke to the United Nations General Assembly, it was the logical next step for South Korean soft power – which is taking over the world, one country and one superstar at a time

He also spoke about Unicef’s newest youth education and training initiative, “Generation Unlimited”, and urged the audience to speak their minds and love themselves. “No matter who you are, where you’re from, your skin colour, your gender identity – just speak yourself,” he said. “Find your name and find your voice by speaking yourself.”

At a meeting where the global community discusses issues such as climate change, multilateralism and peacekeeping, the question on everyone’s minds was what place K-pop had in international affairs.

In South Korea, a moment’s lip service becomes a balm for men

“In their music, they sing about controversial topics like self [esteem] and mental health,” says Tessa Ariella, a student at Yonsei University in South Korea, who says BTS are just as big in her native Indonesia. “BTS are different to other groups, they reach out to everyone.”

The problem was always the language barrier. Many groups, including Girls’ Generation, Wonder Girls, and even Psy – who was unable to replicate the success of his hit Gangnam Style – all failed to break the US market. “That all changed with BTS,” Gibson says. “BTS has been a big success in the last few years because they put in the work. They played small gigs here, they spent time building an American fan base, and they dedicated themselves to finding success here from the ground up.”

Why is South Korea so intolerant of its gay community?

With their relatively candid – by South Korean standards – approach to life and hardship, as well as their hardworking outreach and social media strategies (the group has more than 16.5 million followers on their extremely active Twitter account), BTS’ recent appearance at the UN demonstrates how the new era of K-pop soft power reaches beyond Asia.

“In Korea, with its extremely high suicide rate and the high level of hopelessness among youth due to high unemployment and the competitiveness of Korean society, BTS are trying to make a difference to their key demographic – young people,” says CedarBough Saeji, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of British Columbia’s Korea Foundation. “Working with [the UN] is a logical continuation of that.”

Soft power is all about attracting a foreign public to be more interested in what your country has to offer, Gibson says. “K-pop is the ultimate soft power tool for Korea because it is performed in Korean, and is quintessentially Korean in many ways. It has the power to make fans want to learn more about the music, about the industry, and about the country it came from.”

K-pop has even helped make learning the Korean language the latest fad in some unlikely parts of the world. In a survey of 20,000 K-pop fans living in Algeria last year, 93 per cent of respondents said they used Korean words and slang in their everyday speech, according to a report by Quartz.

“There are tonnes of studies documenting how K-pop and other cultural products like dramas have increased tourism to Korea and have increased the number of people studying the language,” Gibson says.

Why South Korea’s Jeju wants to show you where the communist bodies are buried

K-pop has more soft-power potential than even American pop music, as it comes with less colonial and political baggage, Saeji says. “K-pop comes from a small country that most countries in the world know little about, a country that was never a coloniser and never waged wars on neighbouring countries,” she says. “It can win or lose on its own merits and attract young people not because they know about Korea, but because the Korean elements in K-pop are new, fresh, and – in a way that American pop culture never can be – neutral.”

Still, while the sight of highly managed Asian pop stars dabbling in diplomacy or world politics can be surprising, regional Asian diplomacy is no stranger to their unique strain of soft power.

Popular Japanese politician Shinjiro Koizumi’s mentions of South Korean girl group Twice while discussing an increase in cultural exchanges between Japan and South Korea last January, brought positive feedback from both nations.

One thing everyone agrees is that idols, in many ways, make perfect diplomats. “Due to their training, they are very careful in front of cameras and tend to have perfect public manners. This makes them well-suited for photo ops,” Saeji says.

In Korean relations, K-pop stars have long played major roles on both sides. From South Korea’s blasting of Girls’ Generation songs across the demarcation line – an activity which drew much ire from North Korea, and which has recently ceased alongside warmer relations – to the recent performances of South Korean acts such as Red Velvet, Ailee and ALi in Pyongyang, experts say pop music has ultimately helped normalise relations between the Koreas.

It’s easy to dismiss K-pop as silly, light, and frivolous, Gibson adds. “Are these K-pop stars ultimately going to change the course of peace on the Korean peninsula? Surely not. But their involvement in diplomacy is a great barometer of inter-Korean relations,” she said. “That power of attraction can be a very powerful tool in international politics if South Korea wields it wisely.” ■