In China puzzle, at least Australia knows itself. The UK hasn’t a clue

Canberra has been thorough in examining its position on a rising China. London’s response is one of complacency verging on indifference

It is a common question: what does China want for itself and its future? The issue following on from this, often in the same breath, is what the country thinks of the outside world and the role it might play in achieving what it wants. Non-Chinese get particularly perplexed by the latter because it relates directly to them. Lord Macartney wrote in his memoirs that when he led the first British Mission to China in 1793, he was deeply puzzled as to what the Chinese he met thought of the outside world, and what they really wanted from him and his mission. More than two centuries later, while everything else has changed, the same bewilderment remains.

It is strange in the modern era, especially since China opened up to the outside world in 1978, how little the second question is turned around and asked back: what do we, as outsiders, want from China?

Early on, of course, in the heady days of initial engagement from the 1980s, the answer may have been “for the People’s Republic to become more like us”. But things have turned out more complex than that.

Australian foreign minister Marise Payne: a China dove, hawk or parrot?

Underpinning this question of what we want from China – and closely linked to it – are more profound, structural queries. What do we feel, what are our sentiments towards this vast, complex country? Even if it did become politically more like us, would we embrace and accept it? Deep down, do we want to know anything about it at all, beyond what we absolutely have to?

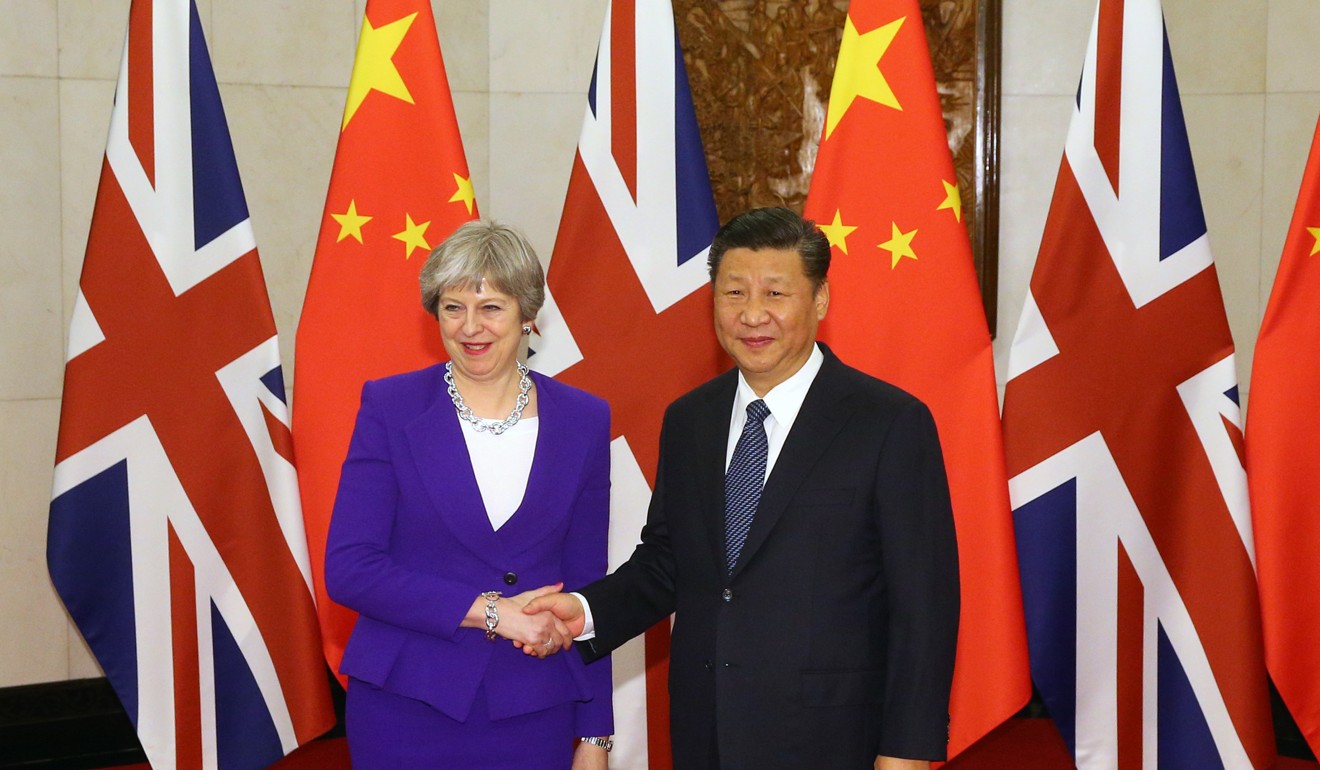

When we compare two cases on this attitude towards sentiment for China – Australia and Britain – we get widely divergent responses. At the very least, one can say that Australia does actually want to know what it thinks and feels about its largest investor and trade partner.

Trump joined China trade and North Korea at the hip, each now drags the other down

For Britain, however, things are very different. British attitudes towards China appear in very general Pew surveys, but these surveys span multiple countries, and are largely devoid of detail. But what do the British actually feel about this partner which, post-Brexit, is likely to figure more in their lives?

Anyone asking this question will be confronted with an enigma. There is no easy way of answering this. There is simply no real data. One can gather some impressions of what the British feel about Americans, Europeans, and others by the amount of films, journeys, and engagements they make with these places. However, China’s cultural and political differences, and its distance, make this a much harder one to call.

A simple explanation in both of these cases is that while Australia has been compelled to ask itself more what it thinks and feels about its massive regional neighbour, due to its greater economic and geopolitical immediacy to China, Britain is not yet in that position. But anyone looking at the almost laconic and sometimes preternatural calmness of the British response to China’s greater impact in the world might describe it as complacency verging on indifference.

This is particularly so compared with the more anxious and frenetic debate about China in the United States, Australia and elsewhere.

It is not so much that the British haven’t been forced to ask themselves what they feel about the new global power – it is more that the British haven’t really regarded it as a question worth addressing in any great detail in the first place.

That posture might be fine at the moment, but post-Brexit, as Britain’s engagement with China is expected to grow, things will quickly become different. At the moment one can argue that the Australian public is well prepared, almost to the point of saturation, to address the various challenges and issues with regard to China.

Australia knows how complex its relations with and its own sentiments towards China are. Britain simply doesn’t.

On gay sex, India has assumed an ancient position. Read the Kama Sutra

Things might go swimmingly in the future and Britain might have the most blessed of links with China. However, this is hardly likely. Even with its closest partners (from Europe to the US), Britain has encountered enough shocks and tribulations in these relations.

What could well happen is that Britain’s real attitude towards China, with all its ambiguity and layers, won’t come forth till a serious problem happens – for instance, a crisis involving Chinese investment or technology used in Britain on nuclear or high-speed projects.

It is likely then that the real sentiments of the British towards their new major partner will come to the fore with force. As Sun Tzu said many hundreds of years ago in The Art of War, the first thing in any engagement with a competitor is to know yourself. On China, the British haven’t even made a start. ■

Kerry Brown is director of the Lau China Institute, King’s College, London, and author of ‘China’s Dreams: The Culture of the Communist Party and its Secret Sources of Power’. Mimi Zou is the Fangda career development fellow in Chinese commercial law at St Hugh’s College, Oxford University