‘I sold my son to I.S.’: how battle for Marawi ripped this Philippine family apart

- Faisal thought he was giving his two boys a chance to escape poverty. Instead, he had been duped by Islamic State extremists into signing them up for battle

Faisal thought he was doing a good thing: giving his son and nephew a chance to escape poverty.

The men offered the boys – Kaheel, 10, and Abdullah, 16 – a chance to go to boarding school in Marawi, the provincial capital, about 20km away. The boys would study Arabic and learn self defence, said Faisal, who spoke on the condition that his family be identified only by their given names.

Not only that, but the men offered to pay Faisal 25,000 pesos [US$480] for each boy.

“What I knew back then was that the money was remitted from another country, an Arab country,” Faisal said. He thought a country in the Middle East was investing in Muslim Mindanao, which is among the poorest regions in the Philippines.

“We needed the money,” said Faisal, who as a labourer earned about US$8 a day and had a family of 10 to support.

The next battle for Marawi: rebuilding after IS

The offer seemed to answer their prayers, but it was too good to be true.

“Abdullah said ‘What we have joined has turned out to be ISIS. They will kill us if we do not engage in battle’,” Faisal said, using another abbreviation for IS. “I told him ‘Find a way to escape.’”

When the boys were taken to Marawi, they soon learned there was no Arabic school.

“I suspected something was wrong, because I saw ISIS men dressed in black,” Abdullah said. “We never learned Arabic. Instead, they told us to go to Piagapo and start training.”

The boys performed basic tasks, like fetching water and chopping wood, before moving on to combat drills using toy guns.

“They told us that when all the first fighters were dead, we would be the next ones to fight,” Abdullah said.

With Faisal’s advice in mind, Abdullah waited until everyone was asleep one night and asked a guard to use the washroom. When the guard wasn’t looking, Abdullah ran, weaving through the trees in the forest and pushing through the tall grass. In the thick of darkness, he found his way home.

But Kaheel had been sent to a different training camp and was in Marawi before the start of the siege.

Gunfire erupted as the militants engaged government troops in street-to-street battles. The air force bombed militant positions, sending bricks, plasterboard and shrapnel flying into the streets.

“Planes and helicopters were dropping bombs. There were explosions and gunfights,” Faisal said.

Kaheel was saved when government troops staged an operation to rescue civilians trapped in the battle zone 10 days into the conflict. When the soldiers secured the building in which Kaheel and a group of other children had been holed up, relatives of those missing, including Faisal, were given two hours to search for their loved ones.

When Faisal found Kaheel, the boy “seemed in a daze … just staring off into space”.

He whisked his son from the battle zone and took him home, where his wife Sarah slapped him across the face.

“You son of a bitch. This is our son. You made him join ISIS,” she screamed. Sarah took Kaheel by the hand and marched out of the house with him. She stayed with relatives for a month, too angry to face her husband. Finally, he came to find her, begging and eventually persuading her to return home.

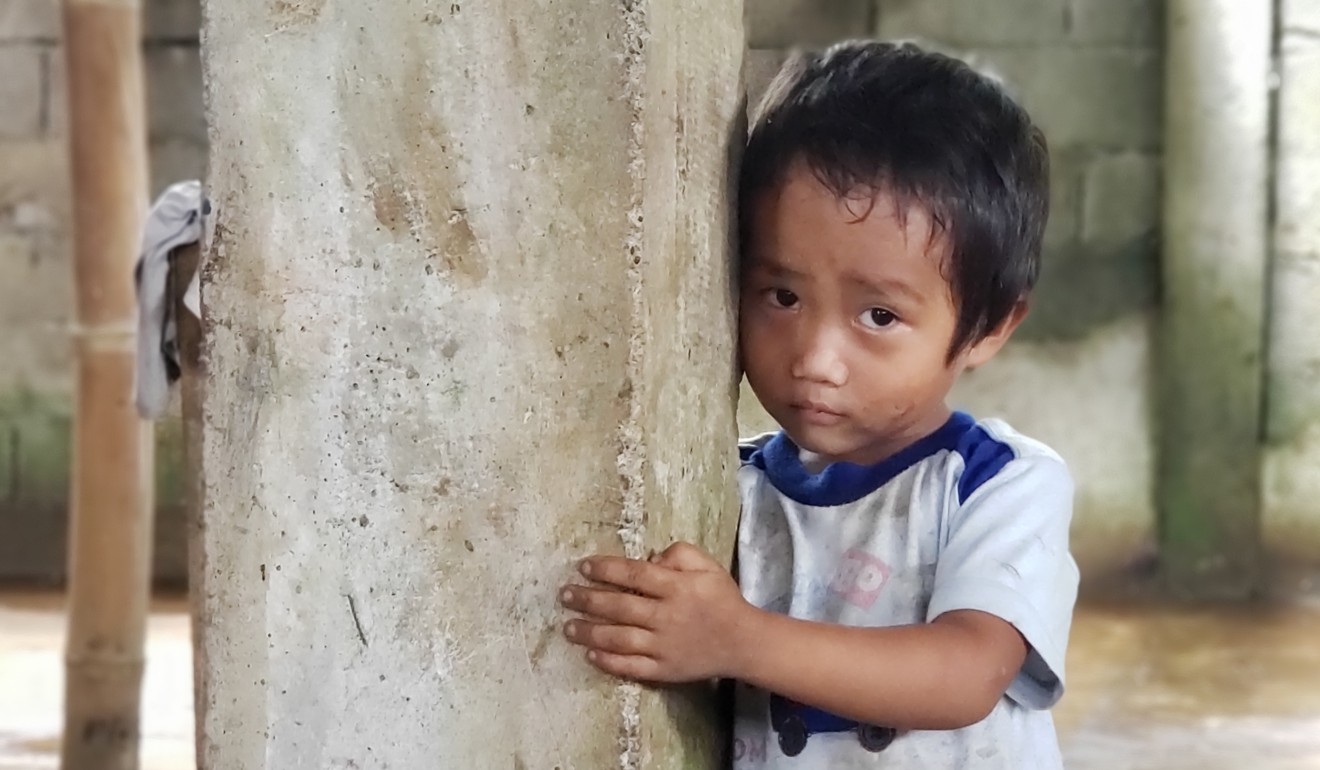

Sarah said that although she had her son back physically, he was not the same cheerful, ambitious boy she had known before.

“The Kaheel we saved was a totally different person,” she said. “He was always in a corner, crying. He was shouting ‘Help! Help! Help!’”

Chinese cash, American muscle, and Marawi’s discontents

The family could only watch over an agonising two months as Kaheel slowly deteriorated, unable to deal with the trauma and slowly starving himself to death.

“He kept crying and crying. Then he became weak, stopped eating,” Sarah said in a broken voice. “He kept crying and crying because of all the shootings that he saw. Then we brought him to the hospital. Three days later he died there.”

When asked to elaborate on the kind of boy Kaheel was, Sarah broke down. It was too painful to talk about.

Faisal is now haunted by regret. “Whenever I think about it, it hurts here,” he said, pointing to his heart. “Of course, I can’t forgive myself. It’s like you said, it’s as if I sold my child.”

The family is hardly the only to have suffered such an ordeal. There are no official figures for the number of children recruited by the IS-linked militants to fight in the battle for Marawi, but many parents have reported being duped into sending their offspring to be trained as child soldiers.

Civilians rescued during the conflict reported seeing children fighting alongside the extremists. Rescued hostages said children were assigned to guard them. Videos posted on social media by the militants during the battle featured children holding weapons.

Abdullah said there were about 50 other young men and women at his training camp. In some cases, their parents had been given money and a promise that their child would receive an education. In others, a recruiter would make friends with the parents and “help them out” financially.

A few months later, more money would be offered in return for the child. The families targeted were poor and uneducated, the recruiters capitalised on desperation.

‘I RECRUITED FOR I.S.’

Poverty was behind Faidah’s decision to help recruit teenagers to fight for the militants. She was just 16 when the extremists approached her in 2016. Faidah said that at first she was reluctant to help them, but her father was out of work and the promise of money to support her family changed her mind.

“My starting fee was 8,000 pesos [US$150],” she said. “Then later on, it increased from 10,000 to 20,000.”

Faidah recruited about 30 teenagers to train with the militants, including her best friend, with promises of monetary incentives. “The kids I recruited all had backgrounds in Arabic, so they could relate to what we were doing,” she said. “When you join the jihad, it is believed that if you die with them, you will go to heaven. I recruited and told them this is for us, for the prosperity of Marawi. And there was also some income.”

“Had I known the outcome, I would never have done it, because this wasn’t jihad,” she said. “I deeply regret it.”

What now for Duterte’s China pivot as Marawi cements US importance?

Since the siege ended, Faidah has been evading the authorities. “I spend my life now in hiding. I’m always sad, bothered by my conscience,” she said.

Her biggest regret was convincing her best friend to join the militants. Her friend, a girl, was in the main battle zone at the height of the siege and never came home. Her parents have told Faidah she is most likely dead.

“To all those affected, I’m sorry,” she said. “I am one of the reasons why your lives are miserable, your homes destroyed,”

For Faisal, it is his reputation that has been destroyed. When his neighbours learned what had happened, they accused him of supporting IS. The family had to move away from Piagapo to start a new life. Abdullah, now 17, is still angry. “I didn’t know that he sold me,” he said. “I thought I would be studying Arabic.”

To make amends, Faisal is sending Abdullah to school – the only child in his family to be granted such a privilege.

“I never reminisce about it. Instead, I’m focusing on my studies,” Abdullah said. “I want to become a policeman to apprehend those who abuse people and do nasty things – like what happened to me.” ■