With Indonesia’s ‘heresy app’, religious harmony hasn’t a prayer

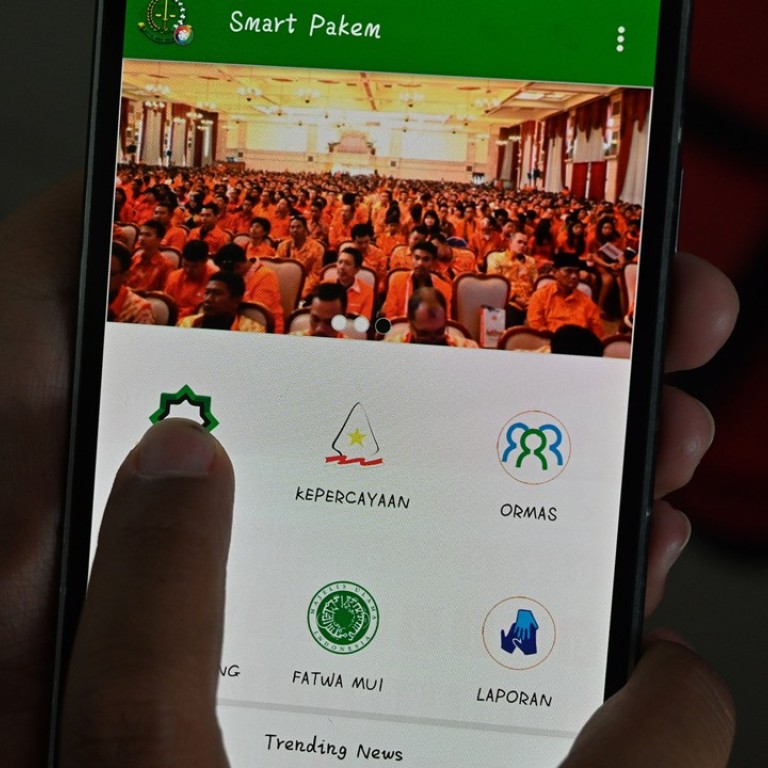

- ‘Smart Pakem’ allows users to report groups practising unrecognised faiths or unorthodox interpretations of the country’s six official state religions

Users of the app can report groups practising unrecognised faiths or unorthodox interpretations of Indonesia’s six officially recognised religions, which include Islam, Hinduism, Christianity and Buddhism.

Information on the app will be updated every two months in accordance with data gathered from the religious affairs ministry, religious leaders and other sources of intelligence, the prosecutor’s office said.

“Now we can digitally keep tabs [on forbidden religions],” said Yulianto, an assistant in the office’s intelligence unit, during the app’s launch event. “Before the app people had to fill in complaint forms, which can be troublesome, so through this app we can easily find out the location of the informant so we can quickly follow up.”

Critics say streamlining the complaints process will only serve to further worsen religious tolerance in Indonesia, which has seen movements against minorities led by religious supremacists gather pace in recent years.

Backlash builds after woman jailed for asking Indonesian mosque to turn it down

The world’s most-populous Muslim-majority nation is largely secular, but Islamic conservatism is on the rise. A recent study by the Indonesia Survey Institute showed that 38 per cent of Muslim respondents objected to non-Muslims performing their religious rites, a slight jump from 36 per cent last year. More than half of Muslim respondents also said that they objected to non-Muslims building religious facilities, a 4 per cent increase from 2017.

Religion is also expected to play a decisive role in the upcoming campaigns for next year’s general elections.

The country’s national commission on human rights, known as Komnas HAM, is calling for the removal of the Smart Pakem app from the Google Play store, where it was still available on Thursday.

But the ministry of communications and information technology has said that further evaluation and assessment of public opinion is required before it can convene a meeting between the prosecutor’s office and Komnas HAM over the future of the app.

Indonesia Islamists threaten to crack down on Christmas hats

“The app could add another degree of discrimination towards religious minorities, mainly towards local religions and new religious movements,” said Halili Hasan, a researcher at the Setara Institute, a Jakarta-based think tank that advocates for democracy and human rights.

“It will give room for people to judge different religious sects and give ammunition to majority groups to persecute minorities. Those who at first didn’t act on the perceived heretical religious [activities of certain] communities now can easily report on ‘the others’ through the app.”

The application is rife with the potential for human rights abuse

According to Komnas HAM, calling a particular religious group “misguided” without providing any evidence also goes against the presumption of innocence - a key principle in the country’s legal system.

Smart Pakem comes under the purview of Indonesia’s agency for monitoring religious beliefs in society, or Bakorpakem, which encompasses teams from various ministries coordinated by the attorney general’s office.

The very existence of such an agency, established decades ago, shows that the state has been intervening in citizens’ private religious affairs for years – in direct violation of the constitution, according to Hasan.

Choirul Anam, commissioner at Komnas HAM, said the Smart Pakem app “is rife with the potential for human rights abuse” and pointed to previous cases where adherents of certain religious sects had been found guilty of crimes without any objective evidence – something he described as a major challenge “in a lawful country”.

Critics of the app have also questioned whether it contradicts a Constitutional Court decision from last year that ruled the state must also recognise traditional beliefs in addition to the country’s six official religions. According to the education and culture ministry, there are up to 12 million followers of traditional belief systems in Indonesia, a country of 260 million people. About 85 per cent of the population is Muslim.

“Native religions and traditional beliefs are still being registered on the national level, so while the process is ongoing, the followers of these beliefs will be vulnerable to prosecution,” said Abdon Nababan, deputy chairman of the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago. “The application was launched at the wrong time. This could lead to social disintegration – particularly in the regions where indigenous peoples still follow traditional rituals.”

Among the most persecuted religious minorities in Indonesia are adherents of the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam, who do not believe that the Prophet Mohammed was the final prophet sent to mankind and have thus been labelled as heretics by Bakorpakem.

The Indonesian villagers who live with their dead

The sect has an estimated 400,000 followers in Indonesia, although their numbers have dwindled in recent years amid a crackdown, which has at times proved fatal.

Another similarly persecuted movement called Gafatar, which combined the teachings of Islam, Christianity and Judaism, was banned by the Indonesian government in 2015. The group, which encouraged followers to sell their possessions and move to rural Borneo, had been applauded by some for successfully improving adherents’ quality of life. Its leaders were charged last year with both blasphemy and treason, and are currently serving three to five-year prison sentences.

“Bakorpakem saw Gafatar as infidels and the state labelled them treasonous, but the court later found that the leaders were innocent on the treason charges,” Hasan said. “They set up a new religion because they were not satisfied with the old religions that they think do not solve their daily problems.”

With legal protections for religious minorities and traditional beliefs still in limbo, human rights activists have demanded President Joko Widodo take action to maintain the country’s traditional stance of unity in diversity.

“Bakorpakem should be dismissed,” said Hasan, of the Setara Institute. “We are asking the president to discipline his subordinates whose programmes exacerbate intolerance against religious minorities, what I’m worried about is that the president is clueless about this current [religious] dynamic.”