The face of fake news: plastic surgery hoax becomes latest disinformation scandal in Indonesia ahead of 2019 poll

An opposition campaigner’s bizarre deception has shone a light on the problem of online misinformation in the world’s 4th most populous country

An Indonesian anti-government activist’s secret plastic surgery procedure has spiralled into the country’s latest fake news scandal ahead of next year’s presidential polls and bruised a former army general’s ambitions to unseat incumbent Joko Widodo.

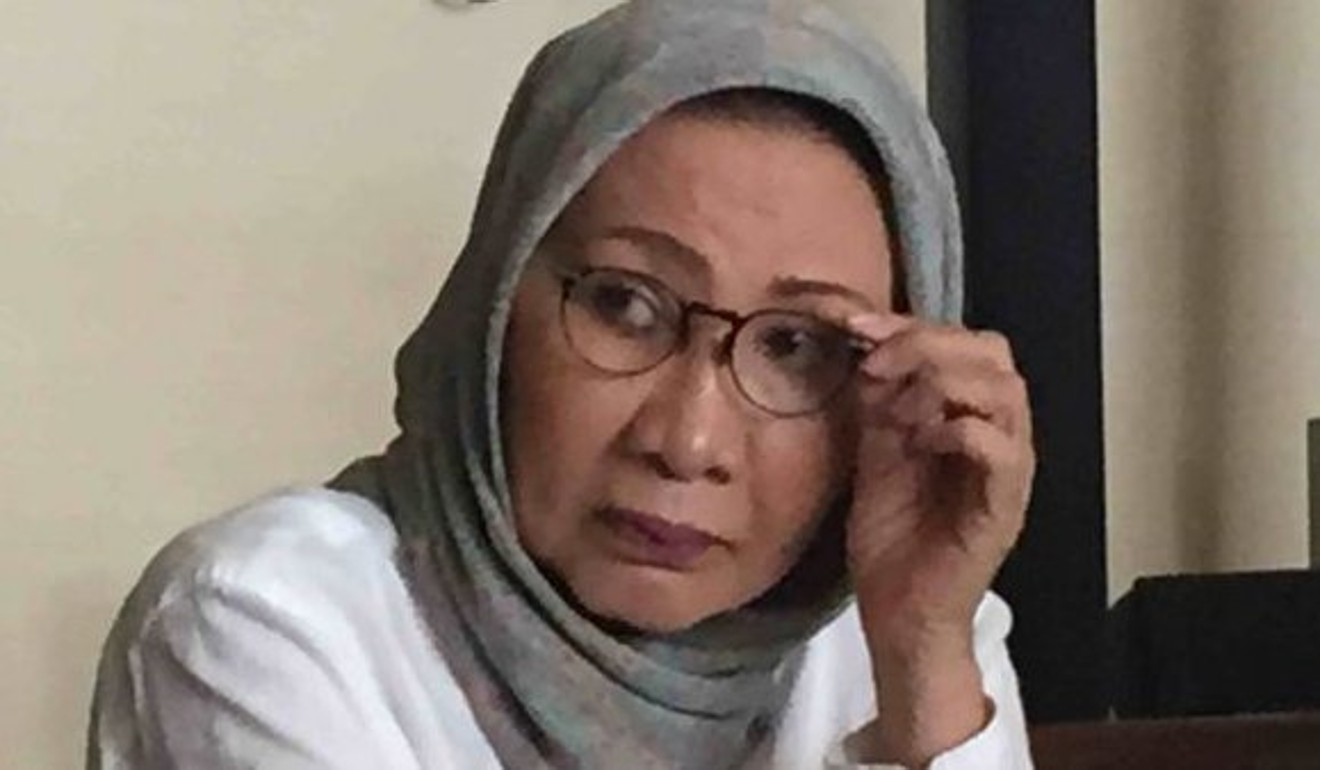

The bizarre case began last month when former actress Ratna Sarumpaet, 69, a member of ex-general Prabowo Subianto’s campaign team, told family that her swollen face and eyes were the result of a politically motivated attack.

Ratna claimed that three unidentified men had assaulted her on September 21 in Bandung, a city two hours from the capital Jakarta.

Photos of Ratna went viral on the internet, with Prabowo springing to her defence. In a news conference, the presidential challenger said Ratna was “traumatised” and he would speak to the police chief about the “human rights abuse”.

One by one, Prabowo’s political supporters, including Muslim leader Amien Rais – a key figure in the reform movement that forced the resignation of President Suharto in 1998 – voiced their support for Ratna and demanded an investigation into the assault.

But in a bizarre twist, a tearful Ratna came clean following a police investigation that unearthed images of her checking into a hospital for face liposuction.

Meet Malaysia’s Syed Saddiq, 25, youngest cabinet minister in Asia

“I needed a reason to explain my bruised face to my children, so I told them that I got attacked,” she admitted on October 3. “I never thought that I would be stuck in this stupidity.”

She continued: “I’m sorry that I lied about this. I hope everybody affected by my lying can accept the fact that I am just a human. This time I have created the best hoax … scandalising an entire nation.”

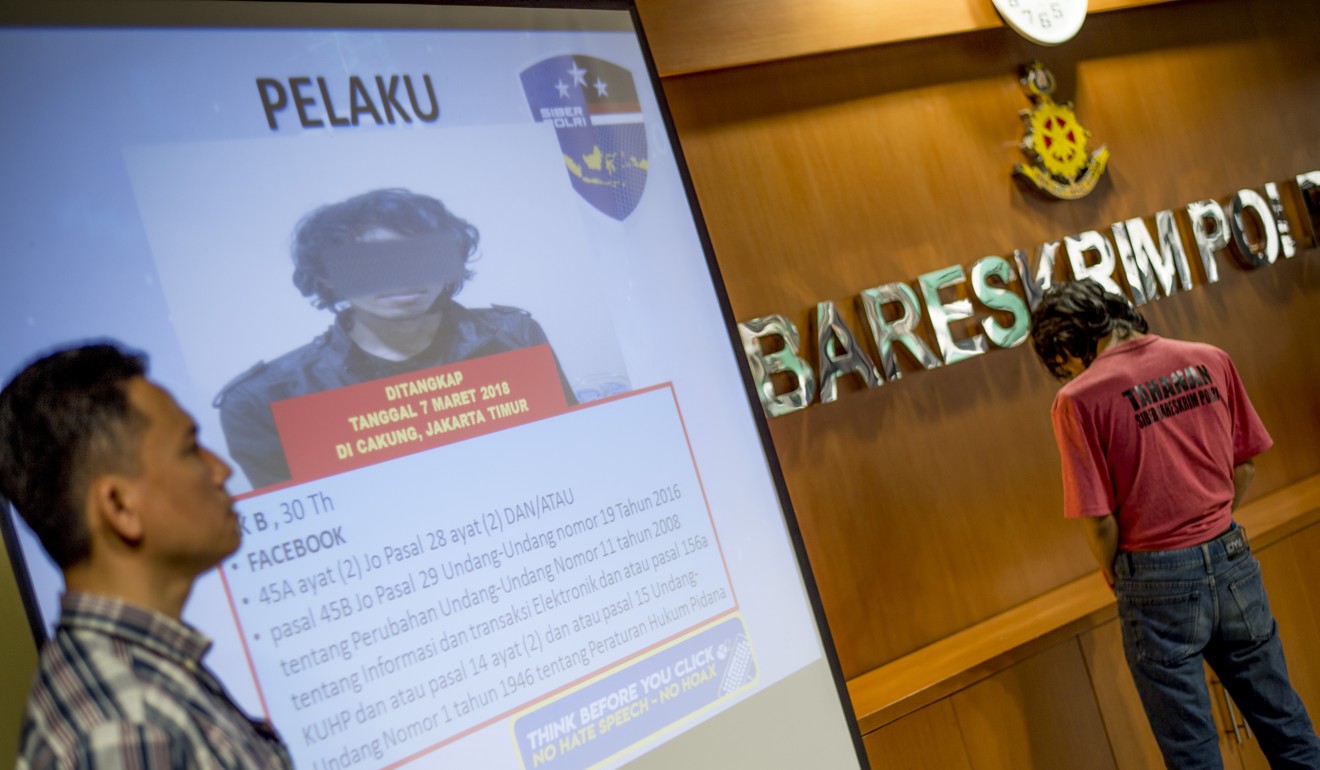

Ratna, who was forced to resign from Prabowo’s campaign team, has since been detained and charged under Article 14 of the criminal code for spreading fake news. She faces 10 years in prison.

Police have alleged that she paid the 90 million rupiah (US$5,913) cost of the surgery from a bank account set up to channel donations to relatives of the victims of a June ferry disaster in which almost 200 people drowned. Her lawyer has denied the misuse of funds.

Prabowo has apologised to the public for “amplifying something where the truth had not been verified“.

Analysts said the deception could deal a blow to Prabowo and his vice-presidential running mate, businessman Sandiaga Uno, who have trailed behind Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, and running mate Ma’ruf Amin in opinion polls.

Jakarta-based pollster Indikator recently found that nearly 58 per cent of Indonesians favoured Widodo as the next president, compared with 32.3 per cent who support Prabowo.

Philippines’ inflation crisis: will Duterte feel the pinch?

“Ratna Sarumpaet’s hoax shows that political hatred and black campaigns are still used for campaigning,” said Septiaji Eko Nugroho, founder and chairman of Mafindo, a community dedicated to combating misinformation. “There seems to be a ‘justify all means’ approach among political elites in order to win … this polarisation will remain until the presidential election is over.”

But with the Widodo government grappling with an economic downturn and its biggest currency depreciation since the Asian financial crisis last month, the opposition has an opportunity and time to make up ground before the April 17 election.

“The impact for Prabowo would be greater had this happened in 2014, when [presidential] campaigns were only six weeks,” said Hendri Satrio, a political analyst in Jakarta. “While legally the case is ongoing, I think that Widodo’s supporters can’t afford to keep bringing this up as it could backfire and generate public sympathy towards Prabowo.”

Meanwhile, Indonesia continues to debate how to grapple with the insidious spread of fake news, which is exacerbated in the country of 260 million by poor digital literacy and growing religious and racial intolerance.

Disinformation has spiked in hotly contested polls since the 2014 presidential election, when Widodo was a regular target of unsubstantiated claims that he was anti-Islam and a communist. Former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic Chinese and Christian, later became a victim when a doctored video circulated appearing to show him telling voters not to be fooled by a Koranic verse that barred Muslims from voting for non-Muslim candidates in elections.He is now serving a two-year sentence in prison, after a Jakarta court last year found him guilty of blasphemy.

Libel, defamation and hate speech are already illegal in Indonesia. While lawmakers have proposed new laws to tackle so-called fake news, human rights activists have raised concerns that too-broad legislation could be used to crack down on political dissent.

Neighbouring countries are also grappling with the issue. In Singapore, a parliamentary committee recently recommended the introduction of new laws to curtail misinformation online. Malaysia already criminalises the reporting of misinformation, although the government of Mahathir Mohamad is trying to repeal the related legislation.

In Indonesia, Mafindo highlighted 230 examples of fake news and hoaxes in the third quarter of this year alone. Most of the cases concerned politics and were spread through Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp.

“There are many online hoaxes that also reached a lot of people, but haven’t blown up in mainstream media [unlike Ratna’s hoax], which is truly worrying,” said Nugroho.

What good is Asean, Indonesia wonders

“Our homework is figuring out how to increase people’s digital literacy. This is a long-term solution to prevent them from falling for disinformation.”

But political elites and religious leaders must also play ball, he said.

“We hope political parties will actively report hoaxes and fake news that cause damage not only to them, but also their rivals,” Nugroho said.

“Many leaders giving sermons are sourcing their information from gossip spread through WhatsApp groups.

“This is poisoning the quality of information being circulated among the public. We need religious leaders to also be involved in our collective effort to stop fake news.” ■