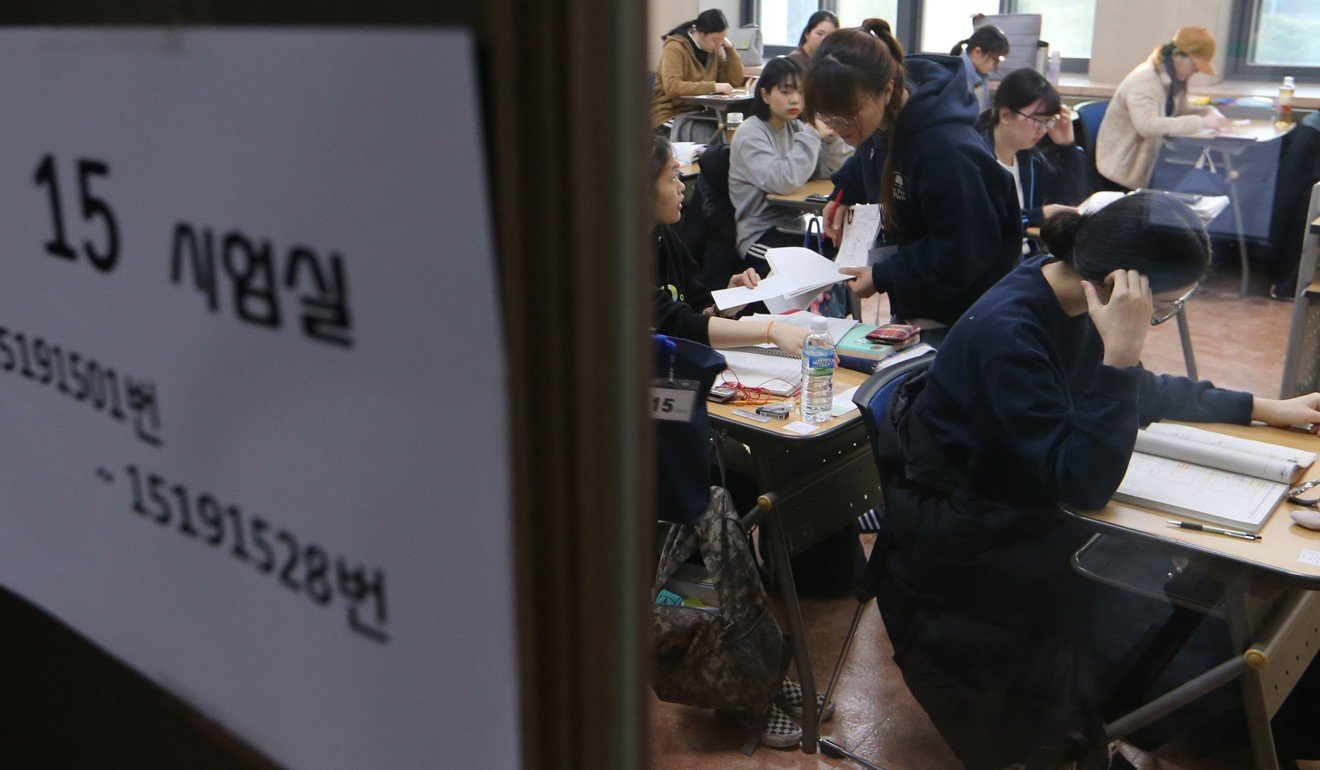

Why South Koreans are trapped in a lifetime of study

- On Thursday, 590,000 high school students took South Korea’s Suneung national college entrance exam

- But for most, even after the ‘life-defining’ test, the flurry of textbooks and stress never ends

South Korea’s annual Suneung examination is a big deal – so big it has repercussions for the whole country.

On Thursday, when the exam was held, aeroplanes took alternate routes to reduce noise, the country’s banks and financial markets started trading later than usual, and buses and subways increased their frequency – all to facilitate smoother traffic and a calmer environment for the 590,000 high school students who took the marathon nine-hour exam, according to Yonsei News.

“Suneung” is a Korean abbreviation for the country’s “life-defining” College Scholastic Ability Test, a standardised national university-entrance exam often likened to a Korean version of the American SATs.

All hail South Korea’s sharing economy (except its taxi drivers)

The exam included tests on subjects such as Korean geography, ethics and thought, law and politics, world history, and countless other topics. Achieving a high score is a testament not only of one’s academic abilities, but also a mark that seemingly defines the entire course of a South Korean’s destiny.

Young people spend the first 25 to 30 years of their life studying, and when they move into the real world and realise life is not a multiple choice test ... that’s already a mid-life crisis

Students begin studying for Suneung from as early as 13 or 14, during their first year of high school, attending extracurricular study academies and cram schools for hours each day after their regular classes – up to 16 hours of studying each day. Many dream of entering Korea’s top-tier “Ivy League” universities: Seoul National University, Korea University and Yonsei University, often referred to by the acronym “SKY”.

Among the hundreds of thousands who take the exam, only 2 per cent will receive coveted offers to study at these universities, according to a BBC report. And while an estimated 70 per cent, according to the same report, will go on to study at other higher-learning institutions, this lifestyle of study continues long past their university days.

OVER-EDUCATED SOCIETY

Millions of South Koreans such as Lee Jin-hyeong are forced to keep studying even after college. “I study every day, from 9am to 1am,” said Lee, who spends most of his time at goshiwon (study rooms) and libraries in Seoul. At the age of 35, Lee, who majored in computer science at university and is studying to take the public-service exam in hopes of becoming a police officer, has yet to begin his first full-time job.

In South Korea, many white-collar roles in industries such as civil service, design, journalism – and even much-sought-after entry-level positions at the nation’s chaebol such as Samsung, LG and Hyundai – all require passing extensive examinations, earning certificates and other qualifications.

Throughout her life, 29-year-old Minji Kim (not her real name) said she had taken more than 50 such “life-defining” exams, including Suneung as well as tests for middle-school entry, special licences, and journalism jobs.

“I started taking these kinds of tests since elementary school,” Kim said. “For some exams, I knew they were potentially life-changing, and so I couldn’t go out on weekends because I needed to spend all my time studying.

Giant killers: the shareholder ‘ants’ taking on South Korea’s scandal-hit Chaebol

“In August 2015, I took my first-ever exam for a journalism job,” she said. “You submit your application and then write an essay and sit for a test so they can assess your knowledge on subjects such as sociology, economics, politics, and even hanja [Chinese characters]. I wrote the two essays within two hours and [then] there was even a ‘drinking test’ – where you have a drink together with the hirer, and they check your behaviour.”

Kim said these tests could take from days up to weeks at a time, and often require applicants to “put their lives on hold” to advance to the next level.

“Some of my friends who live outside Seoul come the day before and book a hotel just to take the exam,” she said. “It happens every weekend for them. It costs a lot, they don’t know when they will get the results and companies don’t compensate for this.”

But even after getting a job, Kim said almost every form of advancement in South Korean professional sectors requires passing an exam. “If you want to get a promotion in your company you also need to take a test for your promotion – you need to achieve a specific grade or licence for instance.”

Koreans are fond of standardised exams as an objective measure of one’s qualifications, according to Shin Gi-wook, professor of sociology and director of the Korean programme at Stanford University.

South Korea’s umbrella movement? How protests against Park Geun-hye exposed cracks in a ‘slave’ democracy

“Koreans value unity and thus feel more comfortable when everyone is judged on the same basis where there is little room for debate and subjectivity,” he said. “The function of exams in modern Korea is that good scores from the exam add credible values to the person’s qualifications, which might be the easiest and the simplest way to secure one’s future in such a highly stratified society.”

In Lee Jin-hyeong’s case, he has taken the public service exam up to four times each year over several years, but has not yet achieved the results needed to move onto the next stage.

“Most people in their 20s and 30s who come to the library like me every day, are studying for similar exams to become government officials, police officers, firefighters. I’d say about 80 per cent of them are in the same situation,” Lee said.

Most exams were offered only once or twice a year at most, Shin said. “Those who don’t get good enough results to get into top-tier universities or companies will need to wait another year to retake the exam.”

Two-thirds of South Koreans aged between 25 and 34 have college degrees, the highest proportion among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. Much like Lee, many of that demographic opt to put their social lives, dating, marriage and other rites of adulthood on hold until they are able to get their first job. Unfortunately, this can take up to a decade.

The more years I’ve spent studying for [my exam], the more this pressure has seemed to build

“Korean society is also very sensitive to age and most companies set an upper age limit for hires,” said Shin, the academic. “Those who fail to prove their worth in the job market in their 20s and 30s will have a much harder time to do so at a later point in their life.”

“There is a great sense of pressure to pass my public service exam,” Lee said. “The more years I’ve spent studying for it, the more this pressure has seemed to build.”

MORE TO LIFE THAN STUDYING?

But in a society many young Koreans call “Hell Joseon” in reference to the lack of social mobility, job opportunities and the overall sense of hopelessness they feel – and where the youth unemployment rate for those between the ages of 15 and 29 was 11.9 per cent in the first half of this year, the highest since 2015 – critics have long questioned whether South Korea’s culture of extreme exams is in fact necessary.

‘My life is not your porn’: South Korean women fight back against hidden-camera sex crimes

Studying in moderation is a good thing, said John Lie, a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. “However, studying all day and into the night as in the case of South Korea – it’s terrible for the children and not at all that functional for society, whether we’re concerned with productivity or happiness.”

While most young Koreans continue to forge ahead in the hope of moving on in life, a small resistance exists. On Thursday afternoon, a group of high school students protested against the unfairness of the Suneung exam system, saying they did not wanted to be “graded” and branded in life like pieces of “beef”.

“We refuse to compete,” the dozen or so students shouted, holding signs bearing slogans such as “University is not [at] the centre [of everything]” outside Seoul’s City Hall.

Experts such as Shin from Stanford say South Korea’s culture of extreme studying leaves young South Koreans ill prepared for real life. “These young people spend the first 25 to 30 years of their life studying for exams, and when they finally move out of their shell into the real world and realise life is not a multiple choice test, and there isn’t always a clear-cut answer to every problem, that’s already a mid-life crisis for them in a way,” he said. “It is both physically draining and mentally not healthy to spend one’s young adulthood studying for exams after exams.”

The obsession with education is partly a legacy of South Korea’s tradition of Confucianism, but it also has a modern social and historical context, Shin said.

“Education was the main source of social mobility in Korea during its developmental period,” he explained. “Koreans believe that without its nation-led obsession with education it could not have achieved the status that it has today in the world economy … Education is at the core of South Korea’s endeavours to succeed.”

Life after Kim: inside the schools catering to North Korean defectors

He adds that there is certainly room for improvement in the current system of college admission and job qualifications.

“For example, there should be diversified admissions criteria such as commitment, leadership, et cetera,” he said. “Some schools do seek to reform their approach to admissions and try to incorporate different criteria but it’s still at a superficial level. For Korean universities and corporations to better compete with their global competitors, we need to see some positive changes to the current rigid system.”

It’s becoming dysfunctional – a “diploma disease”, said Lie from UC Berkeley, referring to the high number of overeducated jobseekers flooding an already overcrowded job market.

“Do modern societies need auto mechanics and plumbers, chefs and pop stars? Obviously, yes,” he said. “Do they need college degrees or advanced certificates? I don’t think so.”

Minji Kim, who now works at a British firm, said even though she did not have to take tests to qualify for her current position, she expects to be studying again in the future.

“I don’t want to take more exams,” she said. “But I think I will have to, as long as I live here.”